After my recent trip to Japan, many of the people I met expressed concern over the future of their country. While the low birthrate and aging population are widely recognized, these are just symptoms of a much broader, multi-faceted crisis. Japan is now even experiencing a rice shortage — a symbolic and practical alarm for its agricultural sector. At this critical juncture, this project will explore the agricultural challenges Japan currently faces and examine potential policy solutions. Updates will be posted regularly as the research develops.

Most people in the west are aware that Japan currently suffers from a low birth rate, which by extension creates the issue of an aging population. A low birthrate is symptomatic of the transition from a manufacturing economy to a service economy, and as Japan had advanced quickly through the mid 20th century, they are making this transition rather quickly. Young people are interested in higher paying jobs, living in cities, and more personal freedoms, which are usually contradictory to traditional family structures. Japanese youth are prioritizing their interests, careers, and finances over traditional family values. We have seen the same transformation in Canada and America, as the average age of marriage and childbirth has significantly increased even in just the past 25 years. A friend of mine who I met on my trip also mentioned that cultural and societal norms tend to drive young people away from agricultural and rural community life. Farms are often owned by the elderly, and lots are small. Because of this, traditional values are enforced through close quarter interactions. Young people may want to work in their own way, with their own freedom, but are discouraged from doing so. My friend mentioned that he would love to listen to music while doing work on his farm, but this would be frowned upon.

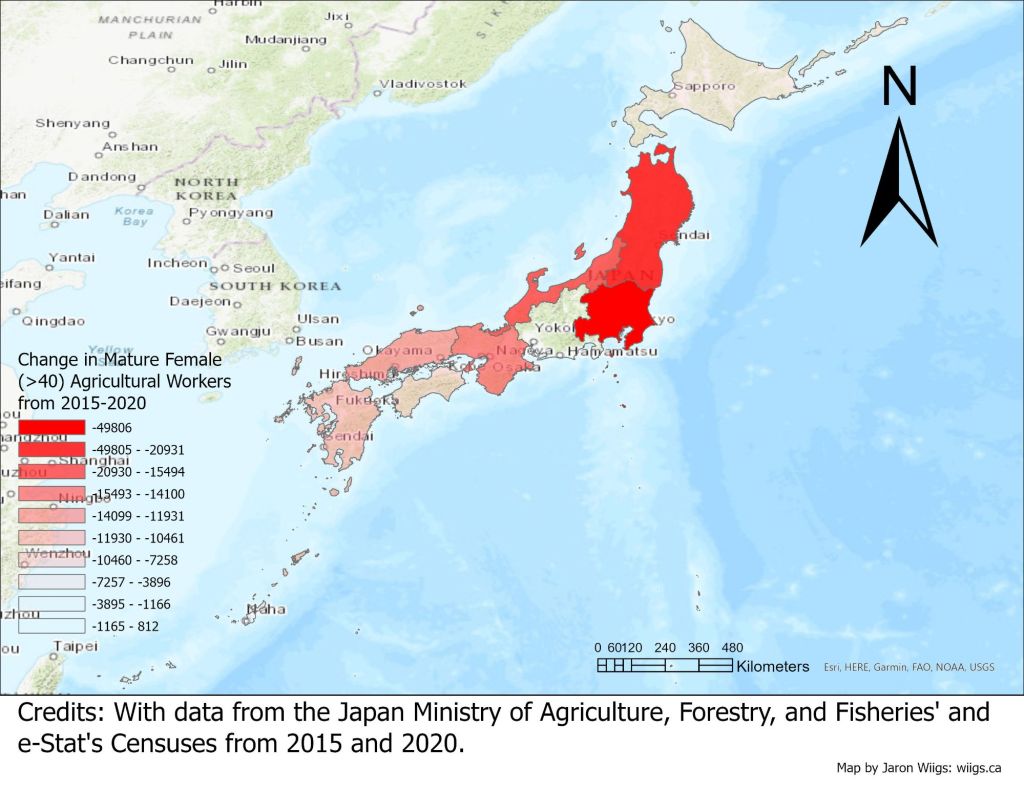

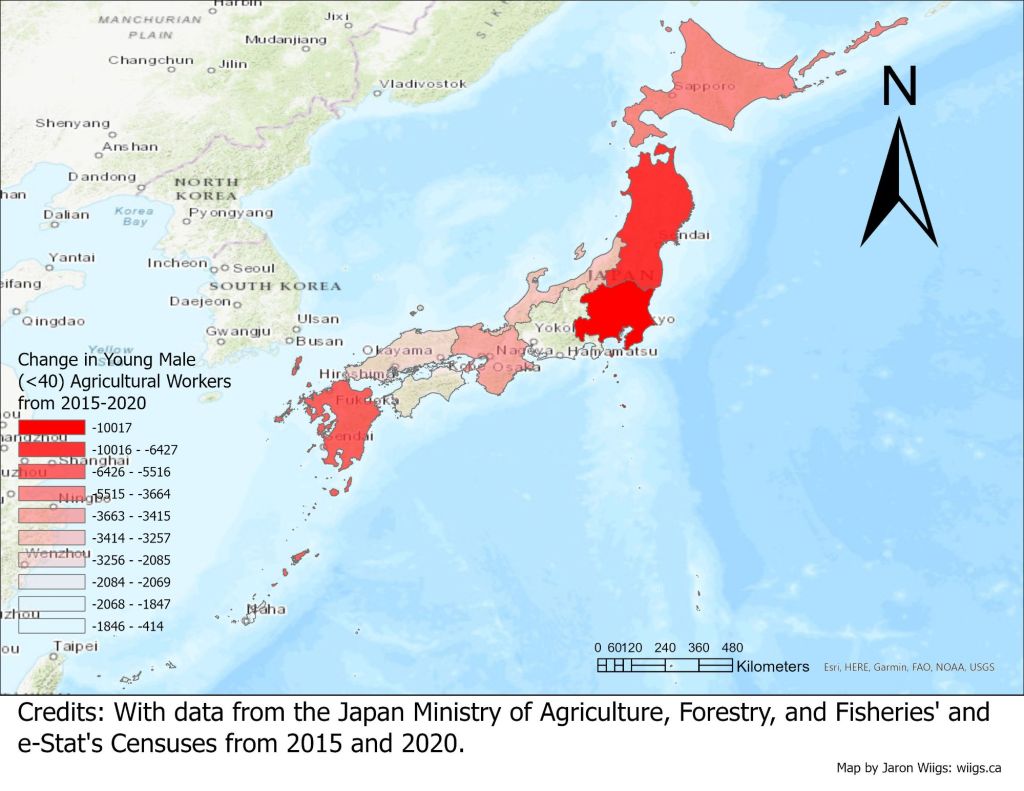

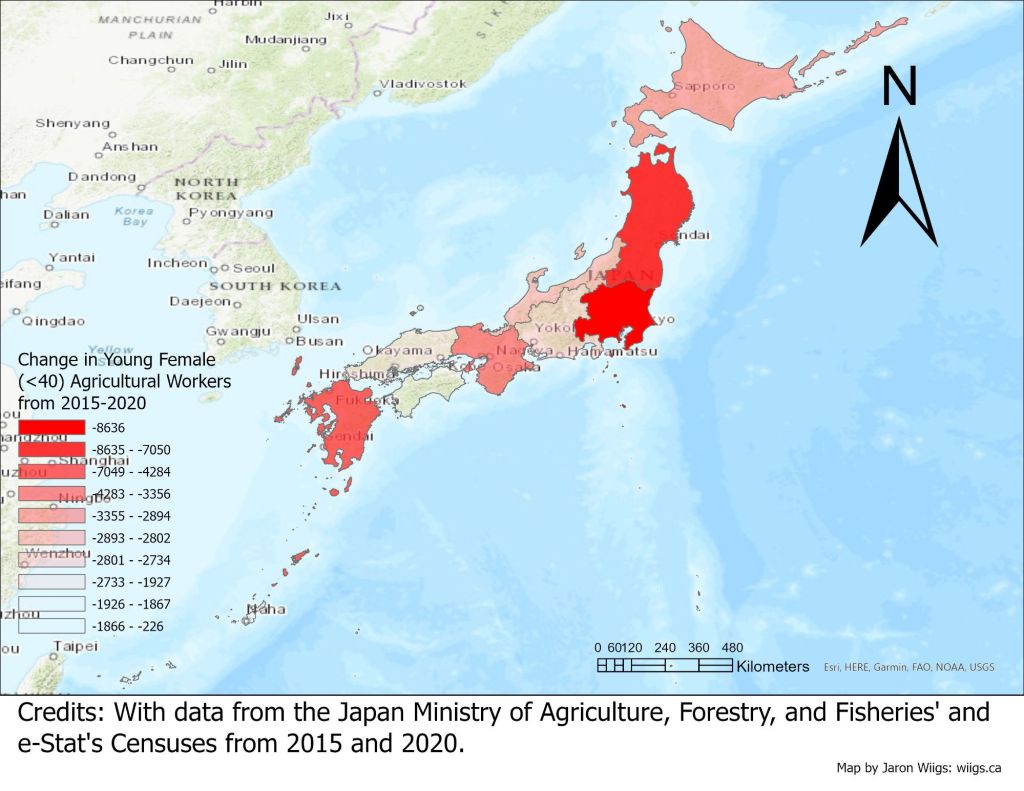

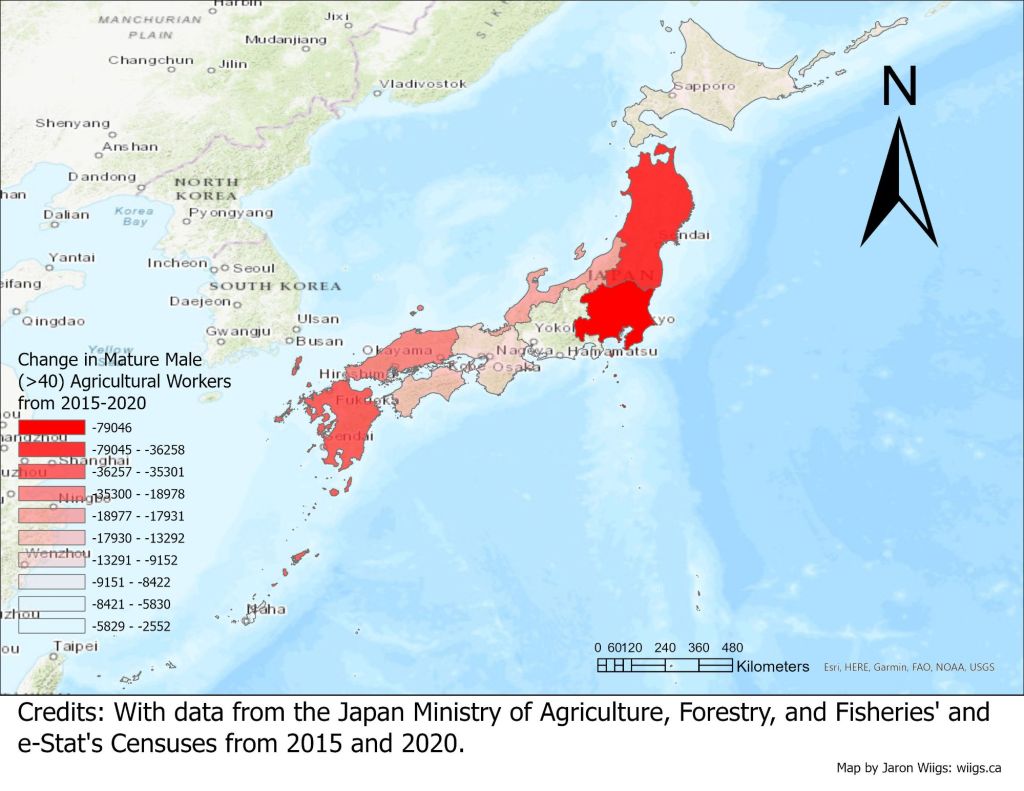

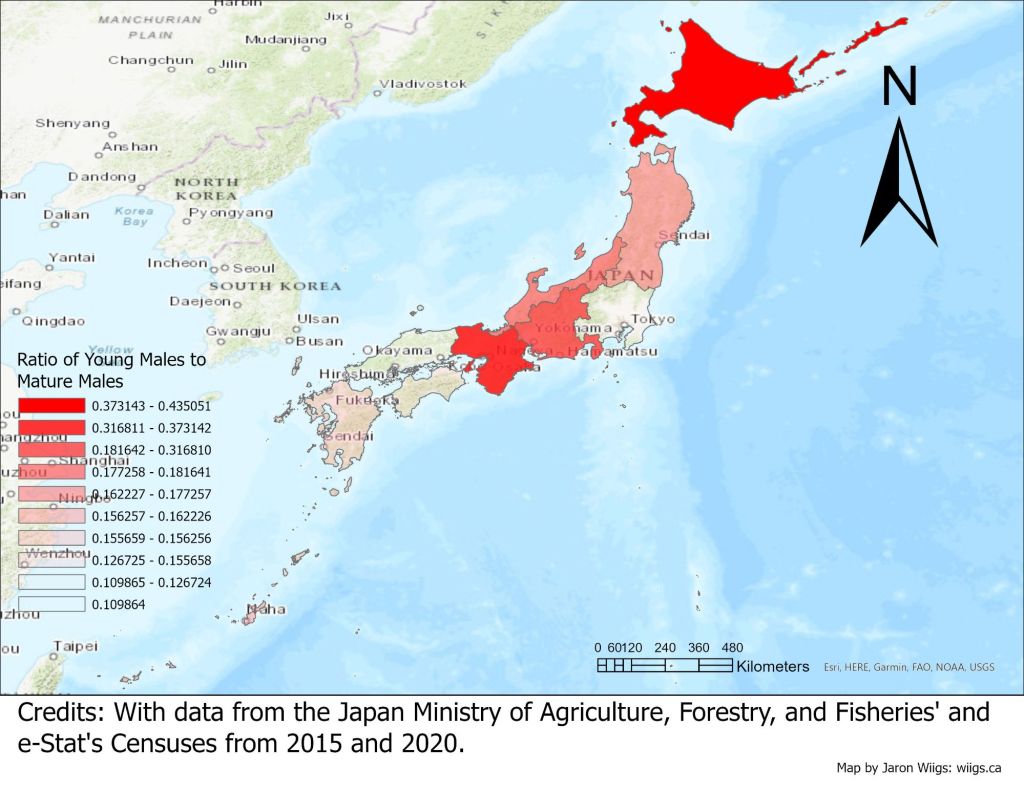

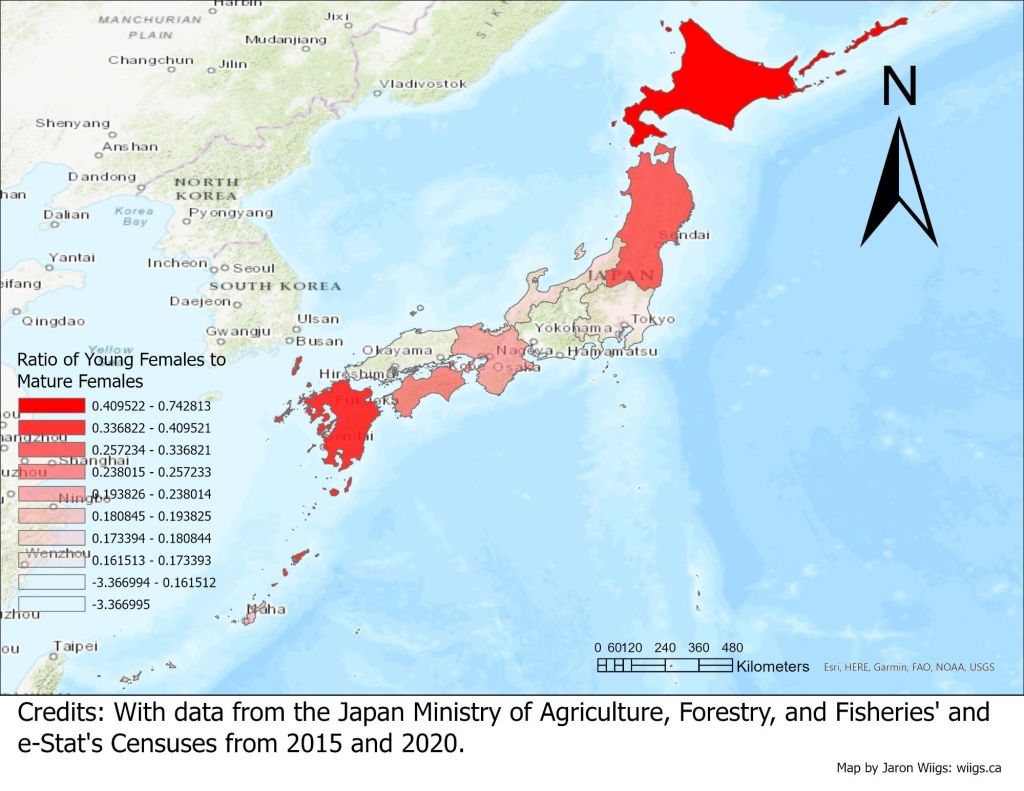

In beginning this project, I’ve decided to map out the change in young male workers (<40) engaged in agricultural work in the regions of Japan using data from the 2015 and 2020 Japan agricultural censuses. I would have liked to map more specifically by prefecture, but the 2015 data was only available by region. Perhaps when the 2025 data is released I will update these maps. The hard work of aggregating data on age and population of agricultural workers is done, so in the following days / weeks I will be posting more statistical maps, based on different analyses. This first phase of research will focus on how and why agricultural work is not popular among young Japanese folk.

We can see from these maps that the movement of men and women is not equal. There are some regions where more young women are leaving the agricultural sector and some where more young men are leaving. Hokkaido for example, saw a relatively stable mature agricultural population, but a very high proportion of those leaving the agricultural industry were young women and men. Moving south to Tohoku we see that the gross number for all age groups and genders leaving is high. Perhaps we can explore the reasons behind this later. Turning to Tohoku’s ratios we can see a comparatively high proportion of young men leaving, and a very high proportion of young women. Kanto experiences the same gross agricultural diminishing as Tohoku, likely due to consistent urbanisation. Kanto differs however, in it’s proportions of young to mature workers. Kanto’s ratio for young males leaving is on the lower side. This ratio is slightly higher for women, but is still not as significant as Tohoku. Moving on to Hokuriku, the changes overall were moderate, with the young female ratio looking quite weak only due to a large loss in mature female agricultural population. In Tokyo, agriculture seems to be alive and well, with relatively consistent mature male and female populations as well as relatively consistent young male populations. Tokai did experience a moderate loss of young female workers, which resulted in a similar ratio of young to mature female emigration as Hokuriku. Kinki was another worrying region, as the change in all demographics save for mature men was high. These maps have not been adjusted for population, which I will do at a later date, but the ratio maps did show worrying ratios of young Vs mature emigration for both men and women, with men being about on par with Hokkaido. Westwards towards Chugoku, we can see the changes in both young male and female agricultural populations become quite stable. This is contrasted by a relatively large decrease in the mature population of both genders. As a result, the ratio maps look quite light here. Shikoku was a very similar outcome, but the ratio of young women to mature women was higher. Kyushu saw high losses in all demographics, but the rate at which they lost young female workers was relatively high. Finally coming to Okinawa, overall losses were quite small, likely due to an overall smaller population. The ratios for losses of young men were about on par with Kyushu, and for women very similar to Hokuriku. Through investigating these maps, I have learned more than I initially thought I would. I will likely investigate patterns of immigration to cities and various other population statistics next. This initial look has sparked many questions, and I feel confident that continued efforts will yield interesting results. I hope you found this research interesting. Until next time!